Imagine there’s no countries

It isn’t hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Imagine all the people

Living life in peace…

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one

I hope someday you’ll join us

And the world will be as one

John Lennon

When I heard about the constitutional amendment on the South Dakota ballot to make all

When I heard about the constitutional amendment on the South Dakota ballot to make all

state elections nonpartisan, I thought of these lyrics.

Imagine there’s no parties?

Believe it or not, that’s sort of what South Dakota is debating this fall. At first blush, it struck me as every bit as unlikely and impractical as what John Lennon sang. But if Amendment V gets a plurality of votes from South Dakotans of all party affiliations this fall, every state office would become nonpartisan.

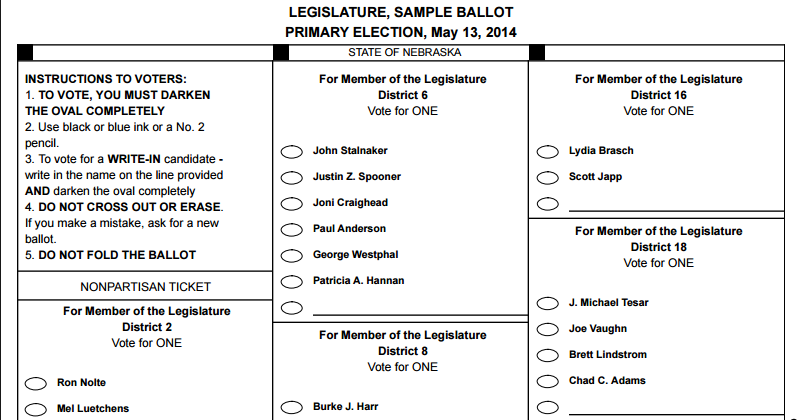

That means that in every election except for presidential contests there would no longer be separate primaries for the respective political parties, party labels would not be used on ballots, and citizens would no longer have their voting restricted due to their party affiliation, or lack of a party affiliation. Instead of party primaries, a single primary contest would be held, and the top two finishers, regardless of their party affiliations, would face off in the general election.

“Imagine there’s no parties. It isn’t hard to do.”

Partisanship Pros

Except that it is hard for me. Very hard. While municipal and judicial elections currently don’t use party labels, I like having party labels on ballots. They give me helpful shorthand clues when I come across an unfamiliar name towards the end of the ballot. For instance, if I want to avoid inadvertently casting my vote for someone who wants to underfund public services or weaken environmental protections, seeing that “D” next to a candidate name on the ballot reduces the chance that I will mistakenly vote for someone who doesn’t share my values.

To be sure, party labels don’t tell you everything, but they give a pretty solid clue about a candidate’s likely positions. I support disclosure in government and governing, and requiring party labels has disclosure benefits.

If party labels weren’t on the ballot, I’d have to do more homework to avoid making voting blunders on the more obscure portions of the ballot. On the other hand, with online resources that are now available, homework has never been easier. By the way, this problem could be lessened if all state and local governments allowed citizens to use smart phones or other types of computers while voting. That’s an antiquated rule that needs to be changed. I need to be able to use my spare brain in the voting booth.

Imagine A Nonpartisan System

Maybe the inconvenience and lack of disclosure associated with a nonpartisan election system would be worth it. I am painfully aware of what extreme partisanship is doing to our politics. It’s making us mindlessly tribal. It’s causing legislators to substitute logic and analysis for blind loyalty to party leaders and their most powerful interest groups. It’s muting the voices of independent and moderate citizens who don’t identify with either of the major parties. It’s making compromise almost impossible.

Drey Samuelson, one of the founders of the South Dakota public interest group championing Amendment V, TakeItBack.org, feels strongly that the benefits of nonpartisan elections and offices greatly outweigh whatever disclosure-related benefits there might be associated with the status quo.

Imagine no closed door caucus scheming. Samuelson says one of the most compelling reasons to keep party labels off the ballot is that it removes partisan control from the Legislature, as it has in Nebraska. Party caucuses don’t exist in the Nebraska Legislature, so policy isn’t made behind closed party caucus doors.

Party caucuses aren’t banned by Amendment V. But Samuelson said that if the nonpartisan amendment passes in South Dakota this fall, there would be strong public pressure for South Dakota legislators to organize themselves in a nonpartisan way — without party caucus meetings and with party power-sharing — as Nebraska has done.

Imagine sharing power and accountability. In Nebraska’s nonpartisan Legislature, legislators from both parties can and do become legislative committee chairs. Because they share power, they also share credit for legislative successes, and accountability for scandals. There is less time and energy wasted on blame games.

Imagine an equal voice for all. TakeItBack.org also stresses that a nonpartisan system will give South Dakota’s 115,000 registered Independents an equal voice in the elections and government they fund, which they lack today. This is particularly important in primary elections, where many of the most important decisions are made.

Imagine a popular Legislature. A nonpartisan Legislature would also very likely be a more popular Legislature.

“People, by and large, don’t like the division, the bickering, the polarization, and the inefficiency of partisan government,” says Samuelson. “They find that nonpartisan government simply functions better.”

In fact, the nonpartisan Nebraska Legislature is nearly twice as popular as the partisan one to the north. A January 2016 PPP survey of South Dakotans found a 36% approval rating for the South Dakota Legislature, while a June 2015 Tarrance Group survey of Nebraskans found a 62% approval rating for the Nebraska Legislature.

A 62% approval rating should look pretty good to Minnesota legislators. Minnesota DFL legislators have a 29% approval rating, and Republican legislators have an 18% approval rating (PPP, August 2015).

For my part, I’d be willing to give up partisan labels on the ballot if it would get us a less petty, Balkanized and recalcitrant Legislature. If Nebraska is predictive of what Minnesota could become, the benefits of such a nonpartisan body would outweigh the costs.

The Minnesota Legislature was elected on a non-partisan basis for about 60 years in the 20th century. There still was a liberal and conservative caucus but the ballots had no labels.